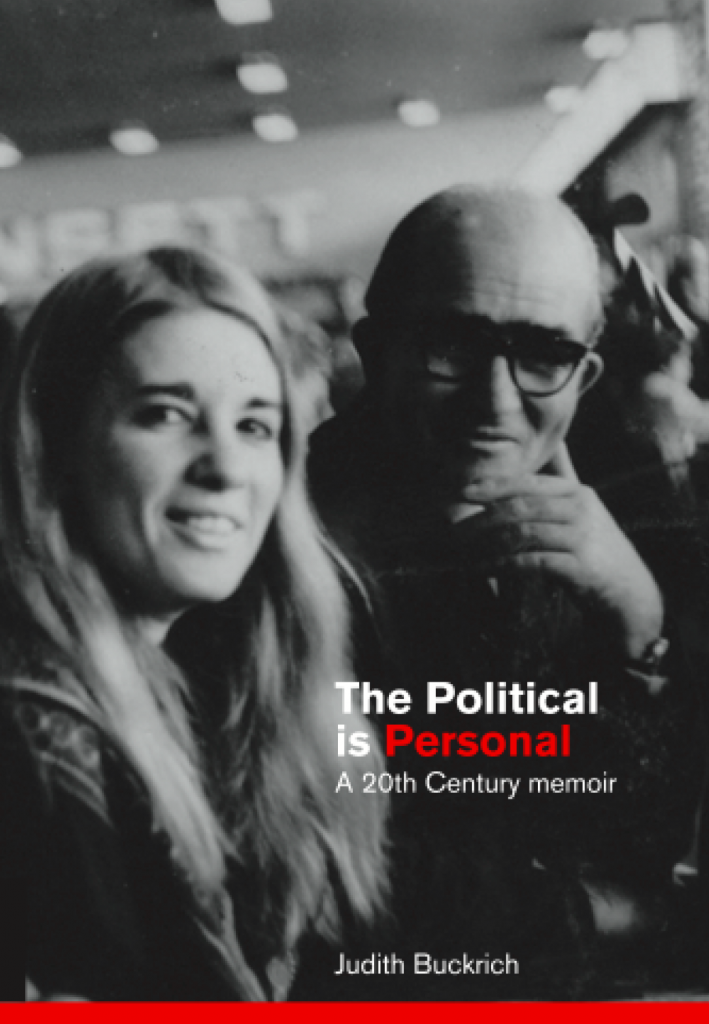

Judith Buckrich, The Political is Personal: A 20th Century Memoir, Lauranton Books, 2016

The title of Judith Buckrich’s memoir, The Political is Personal, is a play on the rallying cry of the women’s liberation movement, “the personal is political”.

In Judith’s case, it is particularly apposite. The trajectory of her life has been shaped by the tumultuous events of the twentieth century – world war, revolution, the Holocaust, mass migration, the Vietnam War and the cultural, social and sexual movements spawned by that conflict.

Judith rode the waves that convulsed Australian society in the sixties and seventies, opposing the war, dropping in and out of university and becoming a cultural radical, feminist and sexual free spirit.

As a child, she witnessed the famous toppling of the gigantic bronze statue of Stalin during the Hungarian uprising in 1956. As an adult, she was in Budapest in 1989 when East German tourists who had refused to leave Hungary were allowed to cross to Austria, an action which precipitated the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Judith, who has made her living from writing plays and histories, was born in Hungary in 1950 of a communist father and Jewish mother. The book started life as a testament to her father, Antal Bukrics, known as Anti, but ended up as a personal memoir.

Born in 1911, Anti emigrated to the US in 1929, a month before the Wall Street Crash. Anti fell on his feet in the large Hungarian community in Cleveland. He found work and a cause, becoming an active member of the burgeoning Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA), writing for its publications and learning how to typeset. With the rewiring of American collective memory during the Cold War, the rich political and social lives enjoyed in communist immigrant communities in the US are all but forgotten.

Post-war, Anti came under the scrutiny of the infamous US House of Un-American Activities and in 1948 was named in a Senate hearing which might have resulted in his deportation had he not decided to join hundreds of other communist Hungarian Americans in going back home to build socialism. He advertised through the Hungarian Jewish Welfare newsletter for a wife and married Judith’s mother, Erika Rosenfeld, shortly after his return.

Erika survived the Auschwitz and Ravensbrück concentration camps and spent months recuperating at the end of the war. It was only when she reached 35 kgs that she was deemed fit enough to travel back to Budapest.

The family enjoyed a fairly well-to-do life in communist Hungary though the relationship between the parents proved difficult from the beginning. During the Hungarian uprising in 1956, the surge in nationalism was accompanied by an outpouring of anti-Semitism and Erika insisted the family leave.

Anti obtained passports through bribing officials and the family joined relatives in Melbourne in 1958. Judith’s second husband, a Hungarian called Gabor Hegyesi, always maintained that Anti must have agreed to be a ‘sleeper’ for the Hungarian government since passports, even with bribery, were simply impossible to obtain.

The Buckrichs, as they became known, settled into Caulfield. In many ways, they were the migrant success story. Both parents worked and they soon acquired a house and a car. Judith, always precocious intellectually, excelled at school and won a place at Mac.Rob, a selective state girls’ high school. She was a member of SKIF, a Jewish socialist youth group. The only blot on an otherwise happy life was her father’s alcoholism.

Partly because of her father, Judith was passionately interested in politics and world affairs. In the early days of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War, she was the only girl in her circle who was opposed to the war. The Aboriginal Freedom Rides in 1965 also stirred her passions and this was again something she shared with her father. In the US, he and other communists had tried to de-segregate a local swimming pool.

Judith took the first of her many lovers at the age of 17 and says: “I enjoyed sex a lot and I was very lucky to live in this new ‘permissive’ age. A young woman could have sexual relations with more than one young man without ‘losing her reputation’…”

Judith failed her first year at Monash University and ended up married at the age of 20. It lasted least than a year and Judith worked and travelled to the US to join her like-minded cousin and became a feminist before returning to Melbourne and completing a degree in drama and media studies at Rusden.

Judith readily embraced the women’s movement. She writes: “In a way, life for women had never been so full of contradictions. Trying to work out how we should behave was very difficult. Behind us, we only had the examples of our mothers, who were kept in line by rules about behaviour spoken and unspoken… The problems of men and women in intimate relationships were not so easy to explore… The circumstances were confused by the hippie idea that ‘love’ could solve every problem, and that individuals should not possess each other – a noble idea in theory, but one very open to abuse by men who ‘wanted to have their cake and eat it too’.”

From the late seventies, Judith started to write short stories and perform in her own plays at places like La Mama and the Adelaide Fringe Festival. One performance included a projected slide of her wearing nothing but a pair of silver boots and a silver strap. Some of these works were written on a farm at Koo-Wee-Rup outside Melbourne, where she lived with Dick Prins, one of her former Rusden lecturers, for six years.

Judith spent much of the eighties travelling and working in short-term jobs such as arts officer for St Kilda Council. In 1987 her relationship with Gabor took her back to live in Hungary where they married.

Judith busied herself with different projects – translating, writing articles, setting up an Australian studies course and contributing to the Radio National program, The Europeans. She worked part-time at a newspaper where the journalists were often arguing the toss with the editors but no one suspected that this presaged the end of communism in the Eastern bloc, starting with Hungary in the summer of 1989.

1989 was the start of a new era for Hungary and a new era for Judith who gave birth to her daughter, Laura, in August that year. They returned with Gabor to Australia in early 1990. Gabor went back to Hungary but Judith chose to stay in Melbourne with her baby and embark on a career as a writer, completing a PhD on George Turner, leading Australian science fiction writer.

At the same time, a chance remark by a friend prompted Judith to write a history of St Kilda Road. This was the first of Judith’s many well-regarded histories of Melbourne. Other histories have focussed on Collins Street, the Port of Melbourne, Montefiore Homes, the Royal Victorian Institute of the Blind, Prahran Tech, and Melbourne University Boat Club. Her history of Ripponlea Village won the 2016 Victorian Community History Awards Local History – Small Publication Award.

Judith writes frankly about her life. After the birth of her daughter, she no longer had the same interest in sex, instead channelling her passion into writing and the work of International PEN, the world-wide Association of writers. She is currently working on history of Acland Street.

RRP $30. Available from Readings Carlton, Readings St Kilda (mail order: www.readings.com.au/books), Collected Works (Swanston Street Melbourne), the Prahran Mechanics Institute and The Avenue Bookstore (Glenhuntly Road, Elsternwick).

Interviews: Judith Buckrich on 0414 905 042; buckrich@bigpond.net.au